Barend Springorum (1742 - 1787)

VOC Sailor and Privateer Commander

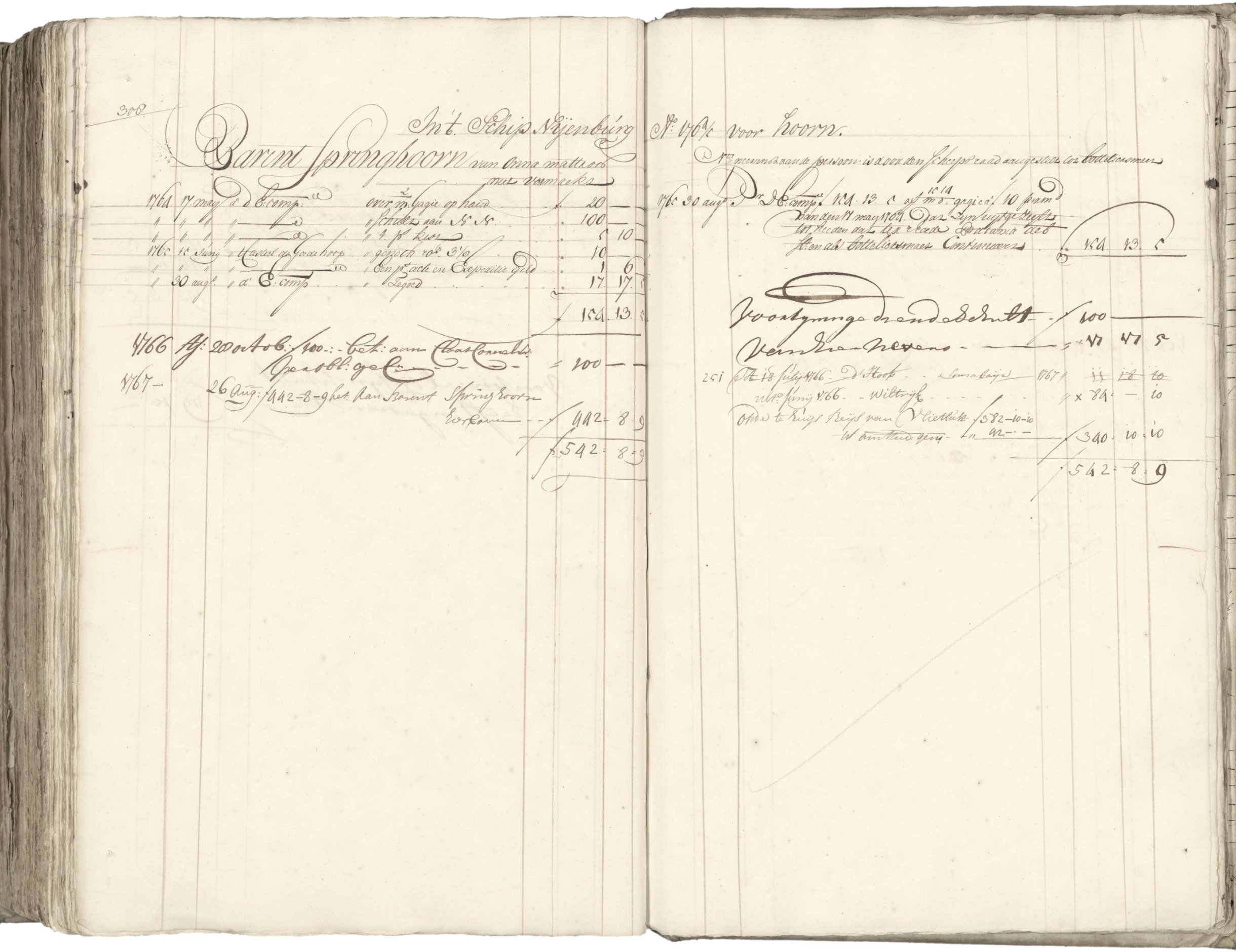

Image: Registration of 21 year old Barend Springorum joining the VoC on May 17, 1764.

Barend Springorum

Barend isn’t a direct ancestor of mine, but his name appears alongside his brother Willem Springorum’s in the Amsterdam city archives several times. The records suggest a close bond between the two—each served as a witness at the other’s children’s baptisms.

Josephus Bernhardus (Barend) Springorum was born to Johann Joseph Springorum and Anna Maria Strotmans. His baptismal record, from the Sint Lambertus Church in Henrichenburg near Castrop, explicitly names Johann Heinrich Springorum and Helena Herdink as his grandparents. This is the only piece of evidence I’ve found so far that directly links Johann Heinrich Springorum to both Johann Joseph Springorum and Barend Springorum.

Image: Babtism record of Josephus Bernhardus Hendricus Springorum (Henrichenburg, St. Lambertus Church, 8 August 1742).

Image: Babtism record of Josephus Bernhardus Hendricus Springorum (Henrichenburg, St. Lambertus Church, 8 August 1742).

Sources:

- Archion: Taufbuch - Henrichenburg, St. Lambertus (1737-1781)

- MyHeritage: Josephus Bernhardus Henricus (Barend) Springorum

Barend Springorum, sailor at VoC

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Amsterdam was one of the wealthiest cities in Europe. It was a center for trade, money, shipbuilding, and skilled work. The city offered jobs and chances to move up in life—opportunities that many rural areas in Germany did not have. Like many others trying to escape poverty, the brothers Willem and Barend Springorum left their homeland when they were young and moved to Amsterdam. At the time, much of the Holy Roman Empire—especially places like Westphalia, the Rhineland, and northern Germany—was facing hard economic times, pushing many people to look for a better future elsewhere.

The name Barend Springorum appears in Dutch records with one especially important entry—his enlistment with the Dutch East India Company (VOC) on May 17, 1764, as a crew member aboard the ship De Nijenburg, at just 21 years old. De Nijenburg was a merchant ship built in 1757 for the VOC Chamber of Hoorn. The archives of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) offer a wealth of information about both the VOC itself and the ship De Nijenburg.

VOC ship De Nijenburg

The ship's first voyage began on April 10, 1759 when it departed Texel, reaching Batavia (modern-day Jakarta) six months later. After sailing to the Coromandel Coast of India, De Nijenburg left Batavia on November 2, 1761 and returned to Hoorn by June 26, 1762.

Image: VOC-ship similar to De Nijenburg

Image: VOC-ship similar to De Nijenburg

Mutiny of the Sulphur Gang

Its second voyage in 1763 would become infamous. Departing Texel on May 8, 1763 with a crew of 236 men, the ship carried a motley assortment of sailors - mostly Germans but also Danes, Italians, Swiss, and even some women. Many had been tricked into service, having been promised positions in the Dutch States Army rather than sea duty, and most lacked any sailing experience.

On the night of June 14 to 15, 1763, during a change of watch, a group of men suddenly stormed the deck of the Dutch East India Company ship Nijenburg, shouting, “German brothers, stand by! Allon, attack!” The mutineers, who had organized themselves under the name "the Sulphur Gang," called for open rebellion against the ship’s officers. This marked the start of one of the most notorious mutinies in Dutch maritime history.

De Nijenburg was heavily loaded with money and gold bars, destined for Batavia where the VOC planned to purchase valuable goods. But the mutineers had different plans. They forced Captain Jacob Ketel to turn the ship toward Brazil. At the time, the vessel was near the Cape Verde Islands. What followed was a journey filled with threats, theft, and even murder.

The mutineers eventually arrived at Cape São Roque, well-supplied with VOC gold taken from De Nijenburg’s strongroom. There, they lived a wildly extravagant life—so excessive that it drew the attention of the local authorities. Their downfall came when a Dutch doctor, who understood their language, overheard their conversations and reported them to the Portuguese authorities. Questioned and investigated, the mutineers were eventually exposed.

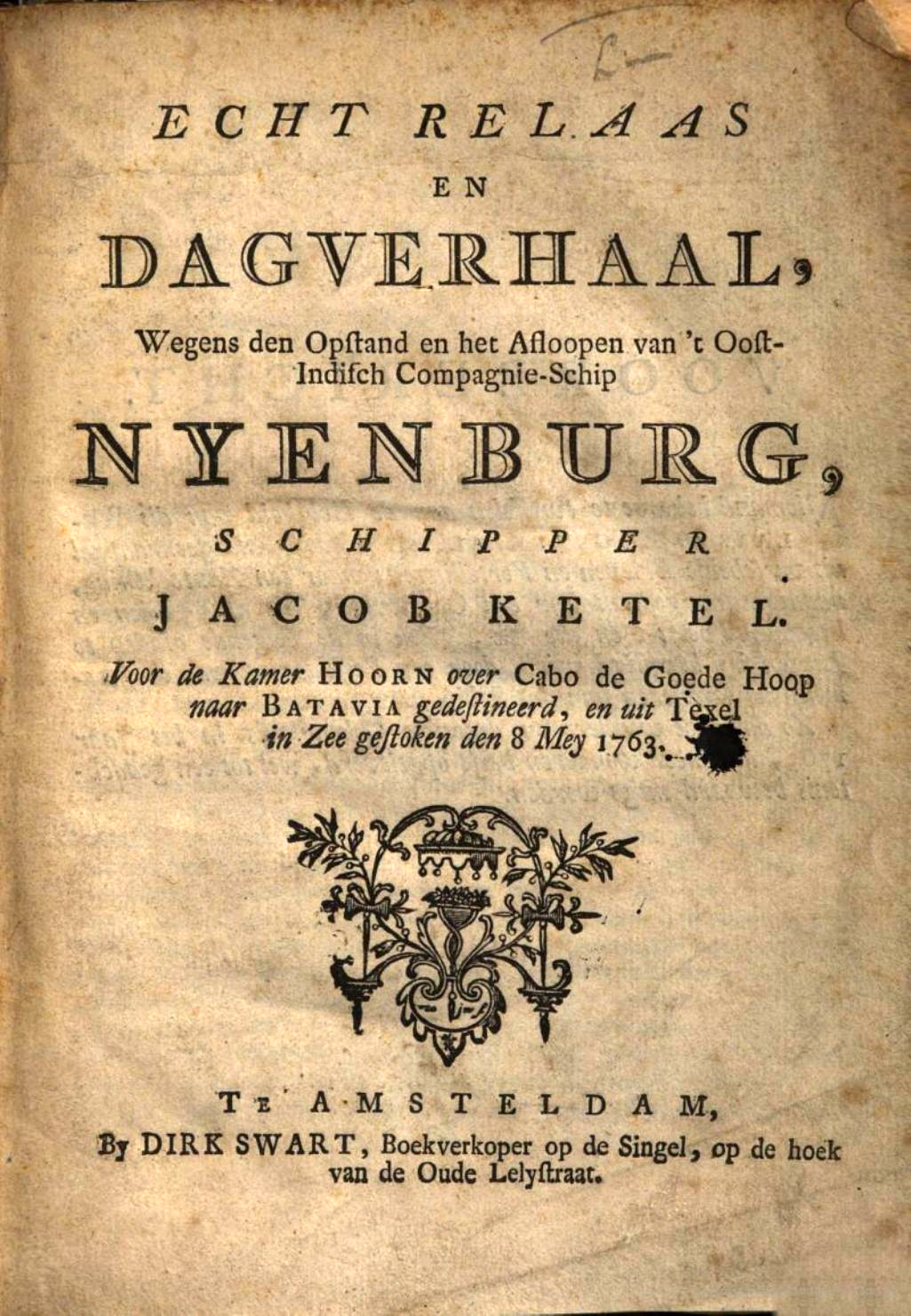

True Account and Daily Journal

Captain Jacob Ketel wrote down everything that happened during the mutiny on De Nijenburg, recording the events in detail as they took place. His notes were later published in a book called Echt Relaas en Dagverhaal. The book gives a clear, firsthand look at life on the ship, especially during the mutiny and what followed.

Image: A detailed account of the Nijenborg’s second voyage was recorded in a book.

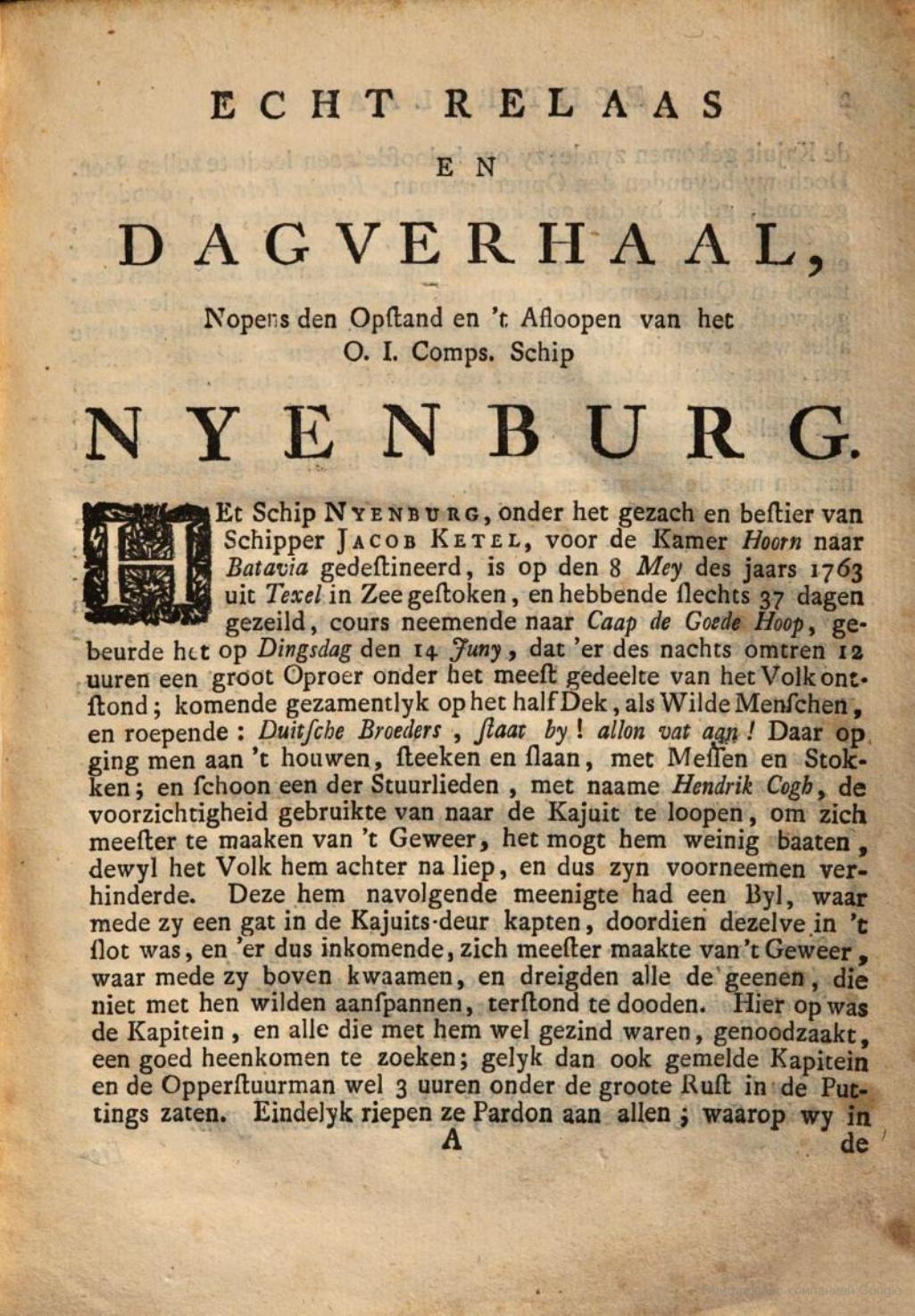

Concerning the mutiny and fate of the East India Company ship Nijenburg

The ship Nijenburg, under the command and direction of Captain Jacob Ketel, bound for Batavia on behalf of the Chamber of Hoorn, did set sail from Texel on the 8th of May in the year 1763. Having sailed but 27 days, and shaping its course toward the Cape of Good Hope, it came to pass on Tuesday the 14th of June, around midnight, that a great uproar did arise among the greater part of the crew.

They came together upon the quarterdeck like wild men, crying out, “German brothers, stand by! Allon, attack!” Thereupon, they began to strike, stab, and beat with knives and clubs. Though one of the mates, by name Hendrik Cogb, had the prudence to flee to the cabin to secure the firearms, it did avail him little, for the men pursued him and thus prevented his intent. The mob that followed him bore an axe, with which they broke a hole in the cabin door—this being locked—and thus forced entry, making themselves masters of the weapons. With these, they returned above deck and did threaten to kill any who refused to join their cause.

At this, the captain and all who remained loyal to him were forced to seek refuge; indeed, the said captain and the chief mate did conceal themselves for full three hours beneath the great chest in the storeroom. At length, the mutineers called for pardon from all; whereupon we in the...

Nopens den opstand en ’t afloopen van het O.I. Compagnieschip Nijenburg

Het schip Nijenburg, onder het gezag en bestier van schipper Jacob Ketel, voor de Kamer Hoorn naar Batavia gedestineerd, is op den 8den Mey des jaars 1763 van Texel in zee gestoken. Hebbende slechts 27 dagen gezeild, koers nemende naar de Kaap de Goede Hoop, gebeurde het op Dingsdag den 14den Juny, dat er des nachts omstreeks 12 uuren een groot oproer uitbrak onder het meeste gedeelte van het volk.

Gezamenlijk kwamen zij op het halfdek als wilde menschen, roepende: “Duitsche Broeders, staat by! Allon, vat aan!” Daarop ging men aan het houwen, steken en slaan met messen en stokken. En schoon een der stuurlieden, met name Hendrik Cogb, de voorzichtigheid gebruikte om naar de kajuit te lopen om zich meester te maken van het geweer, het mocht hem weinig baten, dewijl het volk hem achterna liep en aldus zijn voornemen verhinderde. De hem navolgende menigte had een bijl, waarmede zij een gat in de kajuitsdeur kapten. Doordat deze in 't slot was, konden zij zo binnenkomen en zich meester maken van het geweer. Daarmee kwamen zij weer boven en dreigden allen die niet met hen wilden samenspannen, terstond te doden.

Hierop waren de kapitein en allen die hem goed gezind waren, genoodzaakt een goed heenkomen te zoeken. Zo zaten dan ook genoemde kapitein en de opperstuurman wel drie uur onder de grote rust in de purtings (scheepsberging). Eindelijk riepen de muiters om pardon aan allen; waarop wij in de...

Sentencing of the Mutineers

Authorities captured all the mutineers, with the Portuguese sending some back to Holland and the French transporting others to Suriname. On February 10, 1764 some mutineers arrived at Texel. In Den Helder, the military court under Cornelis Schrijver held trials in March and April, sentencing 17 men: three were broken on the wheel, ten were hanged near Huisduinen—the oldest was 23, the youngest 18—one was made to stand beneath the gallows and then flogged, and two were keelhauled, branded, and banished. Twenty-one men, including nine sailors, the helmsmen, and a boatswain, were acquitted but only paid their wages up to August 2, 1763. Additional trials in Paramaribo led to more convictions, bringing the total number of death sentences to 24.

Image: Execution of mutineers at beach of Kijkduin, Huisduinen (September, 1764)

Image: Execution of mutineers at beach of Kijkduin, Huisduinen (September, 1764)

Voyage Resumed and Fate Sealed

After resuming its voyage on November 23, 1764 with a replenished crew—most likely including Barend Springorum (see below)—De Nijenburg continued the journey to Batavia where the ship arrived in 1765. Eventually—after returning from its third trip—De Nijenburg met its end in 1769, sinking somewhere between Batavia and the Cape of Good Hope.

| Date | Event | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 May 1763 | Departure | Texel, Netherlands | Destination: Batavia |

| 14 June 1763 | Mutiny breaks out | At sea | Crew rebellion |

| 2 Aug 1763 | Runs aground | Coast of Portuguese Brazil | Possibly near Bahia |

| 6 Sept 1763 | Arrival | Cayenne (French Guiana) | Temporary stop |

| 3 Aug 1764 | Arrival | Paramaribo, Suriname | Long stay (~9 months) |

| 23 Nov 1764 | Departure | Paramaribo, Suriname | Destination: Batavia |

| 3 May 1765 | Arrival | Cape of Good Hope | Resupply before Indian Ocean |

| 24 June 1765 | Departure | Cape of Good Hope | Final leg to Batavia |

| 30 Aug 1765 | Arrival | Batavia (Jakarta) | Original destination reached |

| 9 Apr 1766 | Departure | Batavia | Return voyage |

| 20 Oct 1766 | Arrival | Texel, Netherlands | Voyage completed |

Looking at the timeline of the ship De Nijenburg and the date Barend Springorum entered service, it appears that Barend must have been part of the fresh crew that sailed the ship from Cayenne to Paramaribo and eventually to Batavia. The documents mention 144 new crew members who boarded in Cayenne, so Barend was very likely among them. This brings us to the question of how Barend ended up in Cayenne—unfortunately, I haven’t been able to find anything about that yet.

Return to Texel

Barend left Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) on February 5, 1767, aboard the ship Vlietlust. The journey included a stop at the Cape of Good Hope from April 8 to 19. The ship arrived back in Texel on July 22, 1767.

Sources:

- Dutch National Archive: Registration VOC

- Dutch VOC Site: Nijenburg (1757)

- Download: "Echt Relaas en Dagverhaal" (download)

- WikiPedia: Nijenburg (schip, 1757)

- WikiPedia: Muiterij

- Taco Tichelaar: https://tacotichelaar.nl/

- Amsterdam Archive: Muiterij

- Rijksmuseum: Etching print "Executie Muiters Kijkduin"

Privateer Commander Barend Springorum

In 1782, five years after he returned from Ceylon, the story of Barend Springorum takes an exciting turn when, at the age of 39, he is mentioned in notarial documents as an authorized agent collecting prize money for sailors from the exploits of the privateer ship de Spion. Intriguingly, these records refer to Barend as a "Kaapbaas" (privateer commander), indicating he held a position of significant authority in these maritime ventures. The same documents also mention valuable details about the ship involved, de Spion, and its captain, Jan Olhoff, providing strong starting points for further investigation.

Image: Procuratie Likman - Springorum

Image: Procuratie Likman - Springorum

Appeared before me, Nicolaas Brahe, notary admitted to the Honourable Court of Holland, residing in Amsterdam, in the presence of the undersigned witnesses:

Barend Likman, being a young sailor who had served aboard the privateering ship de Spion, commanded by Captain Jan Olhof.

Who declared that he constituted and empowered his privateering commander, Barend Springorum, residing here, specifically and expressly to claim and receive in his name and on his behalf such share as is due to him, the Constituent, from the distribution of monies resulting from the prizes taken and brought in by the said privateering ship, whether in kind or in prize money. [...]

Compareerde voor mij, Nicolaas Brahe, notaris bij den Edele Hove van Holland geadmitteerd, residerende te Amsterdam, ter presentie van de nagenoemde getuigen:

Barend Likman, zijnde jonge matroos, gevaren hebbende op het kaperschip de Spion, gevoerd door Capitein Jan Olhof,

dewelke verklaarde te constitueren en machtig te maken zijn Kaapbaas, Barend Springorum, alhier woonachtig, speciaal en uitdrukkelijk om in naam en van wegen hem, Constituant, te vorderen en te ontvangen zodanige portie als hem, Constituant, toekomt uit de verdeling der gelden, voortkomende uit de prijzen door het gemelde kaperschip genomen en opgebracht. [...]

The World of Dutch Privateering

During the Dutch Golden Age, privateering was essentially legalized piracy. The Dutch Republic issued "Letters of Marque" to privately owned ships, authorizing them to attack enemy vessels during wartime. This practice was particularly common against Spanish, Portuguese, and English shipping in the Caribbean and along the West African coast.

During the tumultuous years of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (1780–1784), Dutch privateers played a crucial role in harassing enemy shipping. Among them was the notorious privateer ship de Spion (The Spy), which operated in the North Sea and Wadden Sea, capturing several English vessels.

"de Spion" and its Colorful Captain

The privateer operation involving Barend Springorum revolved around three ships: de Spion (The Spy), de Dolfijn (The Dolphin), and de Triton (The Triton). These vessels were part of a Kaaprederij (privateering company) led by wealthy Amsterdam merchants Jan Messchert van Vollenhoven, Matthijs Ooster, and Jan Nicolaas van Eys. Jan Olhoff was hired as a captain within this fleet and was given command of schooner ship de Spion, the most notable of the three.

A schooner ship is a sailing vessel with two or more masts, typically rigged with fore-and-aft sails. Schooners were known for their speed and agility, often used for trade, fishing, and privateering. Schooner ship de Spion was a well-armed privateering vessel carrying 12 cannons and a crew of 50 men.

Image: An example of a schooner ship very similar to de Spion. Painting "Ladende schoenerbrik voor anker bij kalm weer" by dutch painter Hermanus Koekkoek (1815-1882), dated 1849.

Image: An example of a schooner ship very similar to de Spion. Painting "Ladende schoenerbrik voor anker bij kalm weer" by dutch painter Hermanus Koekkoek (1815-1882), dated 1849.

The Prize-Taking Voyage of de Spion

In 1782, under the command of Captain Jan Olhof, de Spion captured six English ships: The Elbe, The Fisher, and The Expedition (all three loaded with coal), as well as The John, The George, and The Jenny (carrying barrels and curved timber). Despite this success, de Spion was sold later that same year.

.jpg) Image: Amsterdam Courant 31 aug 1782, Announcement of the auction of two English ships captured by de Spion.

Image: Amsterdam Courant 31 aug 1782, Announcement of the auction of two English ships captured by de Spion.

Disorder Among de Spion’s Crew

The crew members involved in privateering were not exactly the most refined sailors. Still, incidents of violence appear to have been relatively limited. More commonly reported were drunken brawls on shore involving privateer crews that got completely out of hand. One such case occurred on July 24, 1782, when the behavior of the crew of the Amsterdam privateer de Spion, anchored off Texel, prompted a formal complaint from a regiment of Cologne soldiers. However, the complaint did not specify the nature of the misconduct.

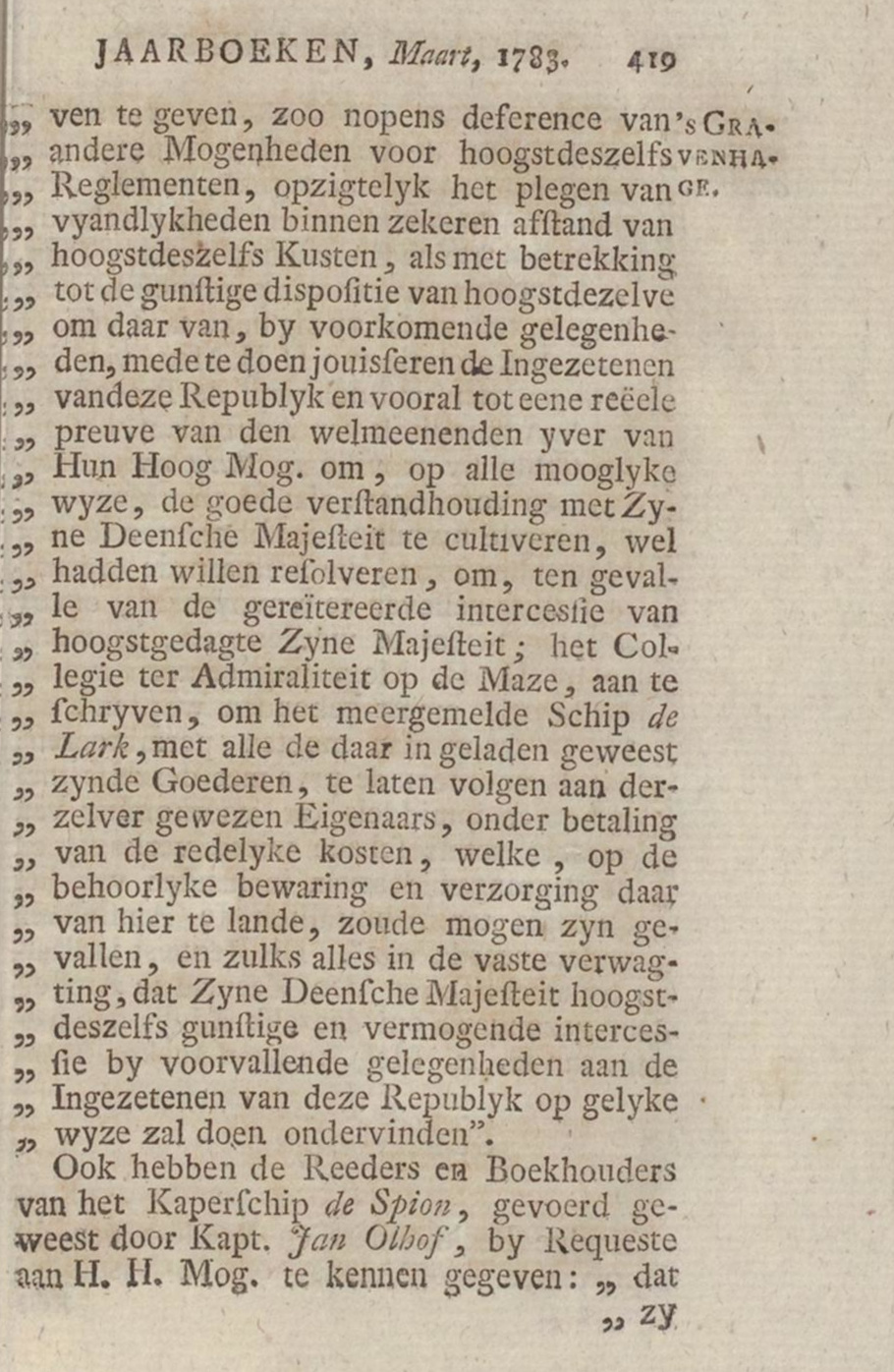

Dispute Over Danish Waters: The Case of "The John"

The Danish envoy filed a protest, claiming that the privateer de Spion had entered Danish waters illegally. Captain Jan Olhof was accused of capturing The John near the Danish island of Helgoland, not on the open sea, and of firing on the island. Olhof denied these claims and provided sworn statements from his crew to support his case. In 1783, the owners of de Spion sent a petition to the States General. They asked for the case to be moved from the Admiralty to a regular court. If that wasn’t possible right away, they requested permission to sell the captured ship and safely deposit the money.

In early 1784, the Admiralty decided that the English ship had been lawfully taken as a prize.

Image: Petition to the States General, asking for the case to be moved from the Admiralty to a regular court. (Nieuwe Nederlandsche Jaarboeken, 18e deel, 1783 p419-420)

The Owners and Bookkeepers of the privateer de Spion, formerly commanded by Capt. Jan Olhof, have likewise declared by Petition unto Their High Mightinesses:

“That they had, with great surprise, learned of new complaints lodged by His Danish Majesty’s Envoy against their said Captain, accusing him of having taken a small English sloop, The John, upon Danish territory; and likewise, that they found themselves burdened by the Resolution of Their High Mightinesses of January last, whereby, pending proceedings before the Admiralty of Amsterdam, the said prize was, by way of provision, to remain in statu quo. They therefore request that Their High Mightinesses, adhering to their Resolution of 5 November 1782, be pleased to remit the case unto ordinary Justice, there to be determined; and, should further deliberation be required, that Their High Mightinesses may permit the aforesaid prize, with its appurtenances, to be sold in the meantime to prevent further loss, and that the proceeds be deposited with the College of Admiralty at Amsterdam, &c.”

This Petition was thereupon sent by copy to the Naval Council at Amsterdam, to render their Advice unto Their High Mightinesses.

Ook hebben de Reeders en Boekhouders van het Kaperschip de Spion, gevoerd geweest door Kapt. Jan Olhof, by Requeste aan H.H.Mog. te kennen gegeven:

„dat zy met groote verwondering vernomen hadden, dat de Gezant des Konings van Deenemarken op nieuw geklaagd had over gemelden hunnen Kaptein, hem beschuldigende, een kleine Engelsche Sloep, The John, op het Deensch territoir genomen te hebben; en tevens dat zy zich bezwaard vonden over de Resolutie van H.H.Mog. van den January, om, middelerwyl de Procedures by de Admiraliteit van Amsterdam, het geprijsd schip by provisie in statu quo te laten: en verzoeken, dat H.H.Mog., persisteerende by hunne Resolutie van den 5 November 1782, die zaak aan de ordinaire Justitie gelieven te renvoyeeren, om by dezelve beslist te worden; en, ingevalle zy by H.H.Mog. nog eenigen tyd in deliberatie moest gehouden worden, dat H.H.Mog. dan mogten permitteeren, dat de voornoemde prijs met deszelfs toebehooren inmiddels tot voorkoming van verdere totale schade wierd verkocht, en de Penningen daarvan in handen van het Collegie ter Admiraliteit te Amsterdam, gedeponeerd; enz.”

Dit Request is daarop by afschrift aan den Zeeraad te Amsterdam gezonden, om deszelfs Advys deswegens aan H.H.Mog. te laten toekomen.

Barend's Role as Privateer Commander

As "Kaapbaas", Barend Springorum would have been responsible for organizing raids, distributing captured loot, and handling the legal aspects of prize claims. His appearance in notarial documents authorizing him to collect prize money suggests he enjoyed considerable trust among the sailors.

Sources:

- Dutch National Archive: Procuratie Likman - Springorum

- Delpher: Advertisement in Amsterdamse Courant

- Delpher: Nieuwe Nederlandsche Jaarboeken, 18e deel, 1783 p419-420

- Pedigree, Paula Lopes

- Kunsthandel Simonis & Buunk: Painting Koekkoek

Family life

Before his time aboard de Spion, Barend Springorum married Willemina Altmans on August 19, 1779, at the age of 37.

It wasn’t until after his seafaring adventures that the couple had children. Their daughter, Joanna Springorum, was born on April 2, 1783, but disappears from the records with no further trace. Their son, Hendricus Bernardus Springorum, was born on November 10, 1784, but died a year later on December 19, 1785. Their third child, Maria Springorum, died on November 28, 1785, likely shortly after birth.

Just a year after losing two of their children, Barend and Willemina drew up a joint will on December 27, 1786, both seriously ill at the time. Only a week later, on January 5, 1787, Barend Springorum died at the age of 44.

b detail.jpg?v=3) Image: Barend and Willemina's notarized last will and testament.

Image: Barend and Willemina's notarized last will and testament.

The Honourable Barend Springorum and Mistress Willemina Altmans, lawful spouses, dwelling within this city in the Binnen Brouwersstraat, both personally known to me, the Notary, and both being infirm of body yet sound of mind and senses, fully capable of making and declaring their will.

Who did declare, having given due reflection to the certainty of death, that they had resolved to dispose of their worldly goods and estate by way of testament or last will; which resolution they, the testators, do hereby carry into effect in the manner following…

De Eerwaarde Barend Springorum en Juffrouw Willemina Altmans, echtelieden, wonende binnen deze stad, in de Binnen Brouwersstraat, mij Notaris bekend, beide ziek van lichaam, doch hun verstand en zinnen welhebbende en gebruikende.

Dewelke verklaarden, door overdenkingen des doods, te hebben voorgenomen te hebben om van hunnen natelatene goederen bij testament of uiterste wille te disponeren: Zoals zij testateuren zijn doende bij deesen in maniere navolgende...

_SMALL.jpg?v=2)

Image: Burial record of Barend Springorum, 5 jan 1787

Sources:

- Amsterdam Archive: Notarial will of Springorum & Altmans

- Amsterdam Archive: Burial record of Barend Springorum

Later that same year, Willemina remarried—to Joannes Hamkolk. Together, they had a son, Joannes Bernardus Josephus Hamkolk, likely named in memory of Willemina’s late husband. Sadly, the child died three months after his birth.